Art offers two great gifts of emotion — the emotion of recognition and the emotion of escape.

Both take us out of the boundaries of self.

– Duncan Phillips, The Phillips Collection

Recently, I went on a field trip to the North Carolina Museum of Art in Raleigh. I went to see A Modern Vision: European Masters from the Phillips Collection. It was the next to the last day of the exhibition and featured paintings by Degas, Van Gogh, Monet, Cezanne and others I have heard of and ones I have not. The styles ranged from impressionism, post-impressionism, expressionism and cubism, collected by Duncan Phillips. It was an incredible experience with unexpected “consequences.”

This visit to the museum was initially intended as a way to do something different, to get out of the house on a cold, winter’s day and to open my eyes and mind to another art form, painting. More than once I’ve heard that as visual artists we should take in, learn about and expose ourselves to different mediums and genres (painting, drawing, sculpting, photography, poetry, etc.). In doing so, we add to our “reference points” of inspiration as we step out of the comfort zone of what we know and do. One thing I learned from this exhibition and in visiting the rest of the museum is that I need to do more “art exploring.” I need to keep filling the well and look for inspiration to bubble up in unexpected ways as I work and grow in my own photography.

THE BEGINNING

For the road trip, I packed a small bag with my camera and several lenses, knowing that a quick turn in the arboretum was on deck, even though the current season is mostly full of bare trees, dried flowers and a few surprises. For the museum visit, I decided not to bring my camera inside. I wanted to be a bit less encumbered. I brought my phone with its own camera, but had no particular plan for what images I would make while there. No theme or pattern was pre-determined. I was there to see some of my favorite painters – Van Gogh, Monet, Degas, Cezanne – and to learn about those I know nothing or far less about. Turns out, I know far less about my favorites than I anticipated. In general, I had no plan but an open mind to whatever unexpected turns presented themselves.

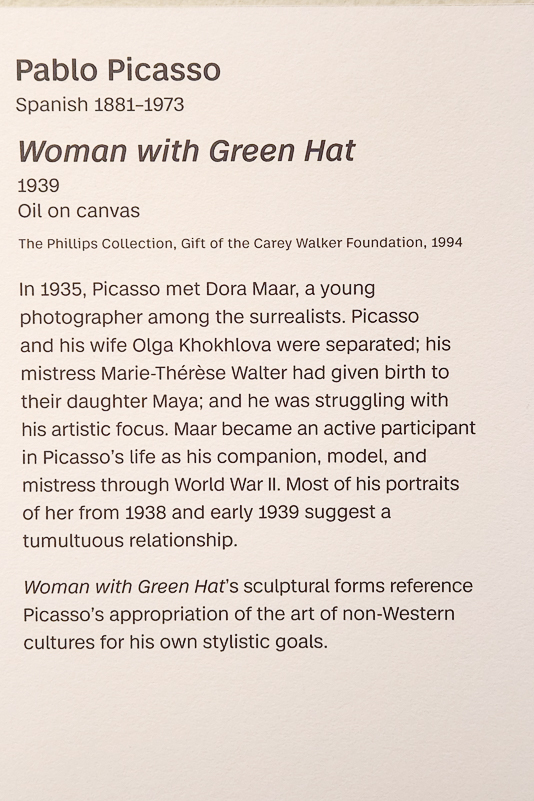

Early in this visit, there was a twist. I thought I would take pictures of the artwork as whole pieces and move along – in a way, “hit and run.” Almost immediately, I was drawn in by the masters’ brush strokes, the colors, textures and patterns and by how those small details came together collectively to create the larger vision and emotions of the artist on canvas. My first frame was “Woman with Green Hat” by Pablo Picasso (Spanish, 1881-1973). The museum label describes succinctly his personal and artistic struggles at that time (1939). I made sure to document the artwork and the museum labels from that point on. This provided additional insight on the artists and the works.

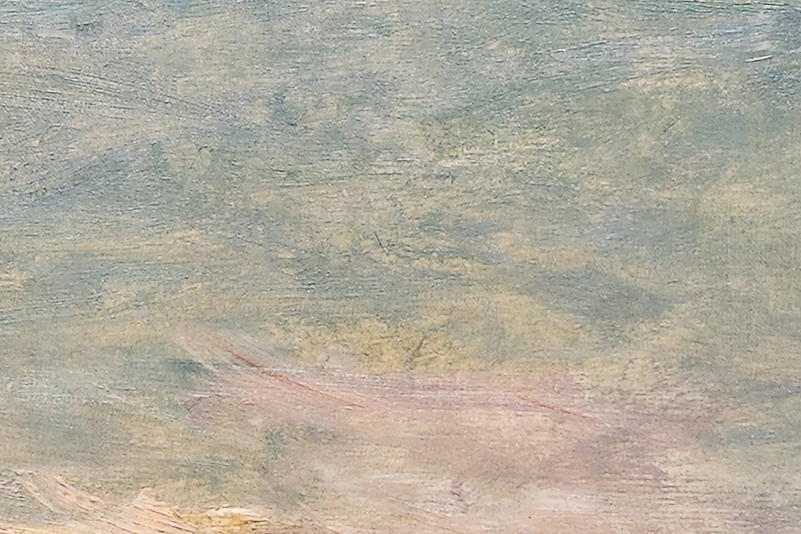

LATCHING ONTO THE BRUSH STROKES

It took very little time for my game plan to evolve and expand. The longer I stood in front of a painting, the more enthralled I was with the brush strokes. I would take an image of the painting as a whole, then several detail shots that showed the colors, textures and strokes, and ended with a frame of the museum label. I didn’t document every piece, only those that were intriguing and fascinating to me.

This pattern began with Oskar Kokoschka, an Austrian painter (1886-1980) and his Courmayeur et les Dents des Geants, made while in Northern Italy. Then came Georgio Morandi, an Italian artist (1890-1964) and his Still Life. Unknown to me, these two artists inspired me to look closer at each piece and to photograph the strokes. Their styles and approaches, within the exhibit, are very different, yet each held my attention longer and made me appreciate the effort and intentions that each painter reflected.

Then, came Claude Monet (French, 1840-1926), someone familiar to me, with an unfamiliar work, Val-Saint-Nicolas Near Dieppe (Morning), 1897. It is one of more than fifty cliff views he produced within 1896-1897. As noted in the label, “Duncan Phillips considered this painting to be a representative example of Monet’s work and one of the most beautiful Monet paintings he had ever seen.” Me? I didn’t even recognize it as a Monet, but was drawn in by the colors, textures and strokes. I was amazed at the intricacies and vision displayed.

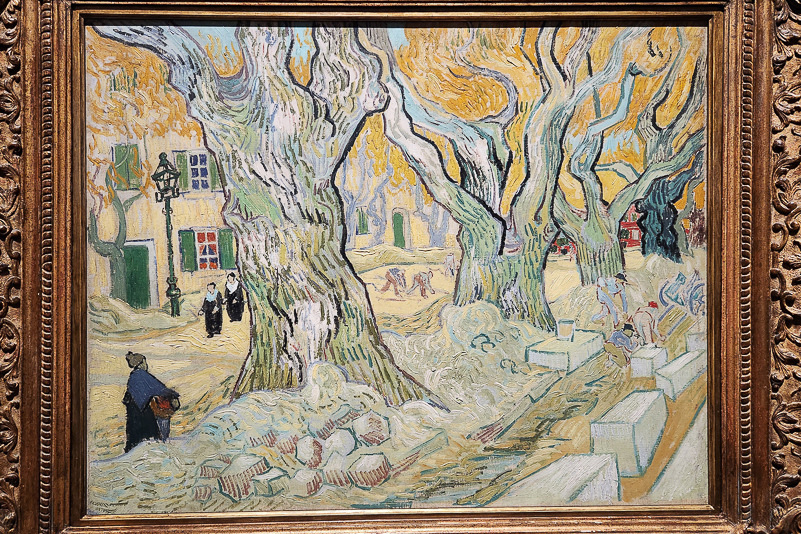

Another surprise came from Vincent Van Gogh (Dutch, 1853-1890) with a painting inspired by a scene he witnessed while staying in a mental hospital in Saint-Remy. He made two versions of The Road Menders (1889), and the one on display was the more finished one. He wrote to his brother Theo, “The last study I have done is a view of the village, where they are working under enormous plane trees repairing the pavement. So there are heaps of sand, stones and gigantic trunks – the leaves are yellowing.” I had never seen this painting before, but Duncan Phillips ranked it “among the best Van Goghs.” I remember reading the letters of Van Gogh and Theo in college and how moving they were. (This painting, in particular, serves as a reminder to expand my horizons in the art world. It makes me want to know more about the work of artists with whom I thought I was familiar.) Sadly, this amazing, but troubled artist shot himself in the stomach and died two days later, seeing himself as a failure. Imagine what more Van Gogh might have created.

THE REST OF THE MUSEUM

In the West Building of the museum, the exhibits ranged from ancient to 21st century and ran the gamut of mediums and genres. It was here that I ran into Elaine de Kooning (American, 1918-1989) and her Red Bison/Blue Horse with its incredibly vibrant color palette, dynamic composition and abstractions. Another “new to me” artist with fascinating colors and brush work. I expect that if I explored more of her work, I would find paintings that are different and surprising.

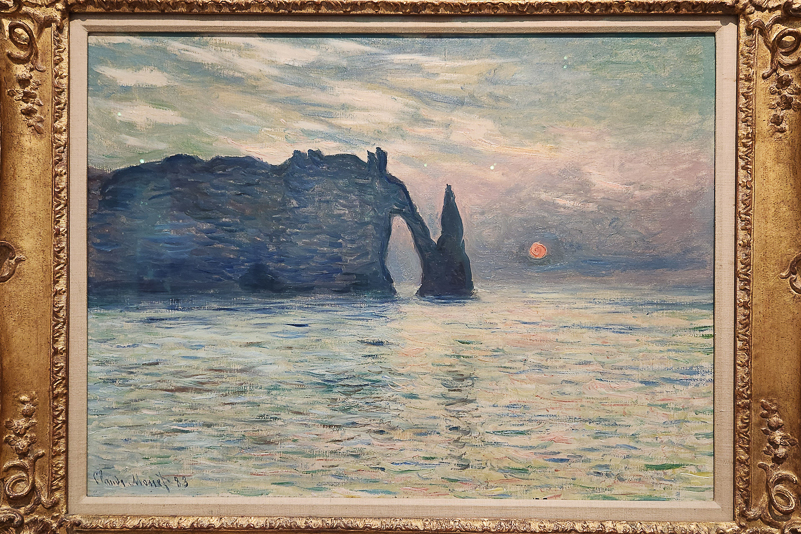

The last set of images I made during the visit was of Monet’s The Cliff, Etretat, Sunset, another unfamiliar work to me (probably due to my attraction to Monet’s flowers and gardens, water lilies in Giverny). Of course, he and all the other artists painted more than the subjects they are widely known for. They experimented, evolved and grew. Their work reflected changes in emotions and mood, colors, tones and approaches to getting what they wanted on canvas. They were influenced by other artists, historical and cultural changes, and by their own personal life experiences, both the triumphs and the struggles. The same holds true for me and you as visual artists whose medium is photography.

THE VALUE OF LABELS

Being honest, when I’ve visited museums in the past, I gave the museum labels at most a passing glance. Perhaps, this is because the only information on them included the artist name and title of work or because I didn’t want to take the time to read them. I focused on the art and moved on.

During this visit, however, I found these labels to be informative, insightful and interesting. I read most of them while I was in front of the paintings, but I also took pictures of them so that I could read them more closely later. I learned about the artists’ styles of painting, composition, their lives in snapshot form along with their artist friends and influences. I also learned a bit about Duncan Phillips, from whose collection these works were curated. I was so intrigued by this collection, and the collector, that I have ordered the book, Master Paintings From The Phillips Collection. I regretted not getting it while I was at the exhibit. I didn’t realize the impact this field trip would have on me. I look forward to learning even more about the art, the artists and the collector.

The labels and their content were relatable and relevant today. I learned that the artists works or styles were not always well regarded. Monet, for example, had a “sketch-like approach that was controversial” and he was “repeatedly rejected from state-sponsored Salons and started exhibiting independently with a group known as the Impressionists, whose works were often critiqued harshly.

Generally, I can relate to what photographers experience in competitions and critiques. Often, images using abstractions, soft focus, ICM, textures and more interpretive techniques are received either with great appreciation or with “less than” impressions. When any judge is more biased toward “pure” documentary image making, they often limit their feedback toward the negative because of their personal bias and lack of appreciation for different. If we present our photography for reviews, feedback or judging, we have to understand the nature of “opinions” and bias. We must put the judges in their place in relation to our work and not be discouraged when something is not received well, scores low or is not understood. We must hold fast to our vision and know that not everyone will regard our work highly.

I learned (or rather, confirmed) from reading these labels that all artists struggle, not always financially, but also personally in their art, their lives, and with the need to express themselves, to be authentic and to find acceptance within themselves. We all, at different times and with different levels of intensity, “struggle” to find our own artistic path as well as acceptance from ourselves and from others.

Some of the artists in the exhibit spent time in prison, others in mental hospitals, and others seemed to have the luxury of spending large blocks of time “doing” their art and painting. They were inspired by each other. They were influenced by nature, landscapes, seascapes, gardens in addition to elements of the ordinary life and personal tragedies. Their color palettes, methods of painting and responses to color and light varied.

The ”why” and “how” behind these pieces of work can be very surprising and unexpected. For example, Pierre Bonnard (French, 1867-1947) would tack canvases to his studio walls and randomly make marks on different pictures and then go for walks to relax and re-energize. Andrew Wyeth (American, 1917-2009) created Winter 1946 out of the tragedy of his father’s death. Symbolism abounds as the hill became to him a portrait of his father, “breathing – rising and falling – almost as though it was my father’s chest.” And the boy chased by his shadow – by death? – “was me, at a loss – that hand drifting in the air was my free soul, groping.” I knew Wyeth’s style and some of his work, but without the museum label, I would have missed the deeply personal nature behind this painting. Did I need to know the backstory in order to appreciate this work? No, but knowing it makes me appreciate it even more.

RELATING THE BRUSH STROKES EXPERIENCE

I’m still amazed at how the brush strokes of these artists engaged and energized and fascinated me. I look at each detail image of the strokes, the paint textures and layers and wish that I could rub my fingers over them. I look at them and wonder what the first brush stroke looked like, the one that led the way for each completed piece. Where did it land on the canvas?

I anticipate this experience to “feed my well” in ways I cannot predict. I am influenced in my photography by what I love (flowers, nature, colors, textures). I am influenced by those whose works and philosophies or approaches inspire me and by those who push me out of my comfort zone. I and my work are influenced by my life experiences, emotions and struggles, some that few will ever know about (or that would ever land on a museum label).

When I photograph and then process images, the methods and results are impacted by my goals, my mood and my emotions as well as my experience with a particular subject. Sometimes, I go dark to accept where I am. Other times, I go lighter to fight against the darkness. Unless you know me well, those personal interpretations of images would likely be missed. Sometimes, I’m simply playing and experimenting with light and dark, with color palettes and textures and creating images that “feel” as I do or how I want them to be perceived and felt. My own brush strokes are made with a computer, but my vision is reflected in the images I create and share.

FINAL WORD ON MY LATEST ART IMMERSION

My field trip to the art museum was impactful in a number of ways. I spent several hours immersed in the works of painters I knew and didn’t know. I didn’t like every painting, whether because of subject matter, color palette or style, but I gained a deeper appreciation for all of them. I focused a lot of my time observing the brush strokes of the artists, taking them in from a distance and in the details, and was fascinated by all of them. As I made photos of the details, I was inspired to consider how I might use them in my own work. One obvious avenue could be to use the brush stroke details as textures and color washes. On their own, the images make wonderful abstracts.

In observing the works, I saw many smaller stories, not unusual for my way of seeing. Many of these smaller stories could stand alone as another painting. It reminded me and reinforced the idea that there are always more stories to be found within the larger story images (landscapes, etc.) that we make. There are intimate landscapes and close-up and macro images to be drawn out of the larger scenes. If we begin with the wider view and then stay longer, long enough, to break it down by moving in and getting closer, we will see those stories in our images. The smaller stories are actually easier for me to find than the larger ones, which may explain my attraction to the masters’ brush strokes in this exhibit.

I cannot wait for the exhibition book to arrive and learn more about The Phillips Collection and this exhibit. I’ve decided that I need to get out more, to find art, take it in and feed the well. I also realize that working from home isolates me from making connections with people and having conversations in general and about art and photography. I was reminded that I need to “do” my art on a much more regular basis. I need to find inspiration anywhere and open myself up more to honoring my vision, appreciating the gifts and sharing with others. I also need to tap into all the art and photography books that are already in my home. There is fertile ground to be cultivated and growth on the horizon.